The ocean is teeming with life. But unless you get up close, much of the marine world can easily remain unseen. That’s because water itself can act as an effective cloak: Light that shines through the ocean can bend, scatter, and quickly fade as it travels through the dense medium of water and reflects off the persistent haze of ocean particles. This makes it extremely challenging to capture the true color of objects in the ocean without imaging them at close range.

Now a team from MIT and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) has developed an image-analysis tool that cuts through the ocean’s optical effects and generates images of underwater environments that look as if the water had been drained away, revealing an ocean scene’s true colors. The team paired the color-correcting tool with a computational model that converts images of a scene into a three-dimensional underwater “world,” that can then be explored virtually.

The researchers have dubbed the new tool “SeaSplat,” in reference to both its underwater application and a method known as 3D gaussian splatting (3DGS), which takes images of a scene and stitches them together to generate a complete, three-dimensional representation that can be viewed in detail, from any perspective.

“With SeaSplat, it can model explicitly what the water is doing, and as a result it can in some ways remove the water, and produces better 3D models of an underwater scene,” says MIT graduate student Daniel Yang.

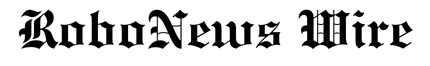

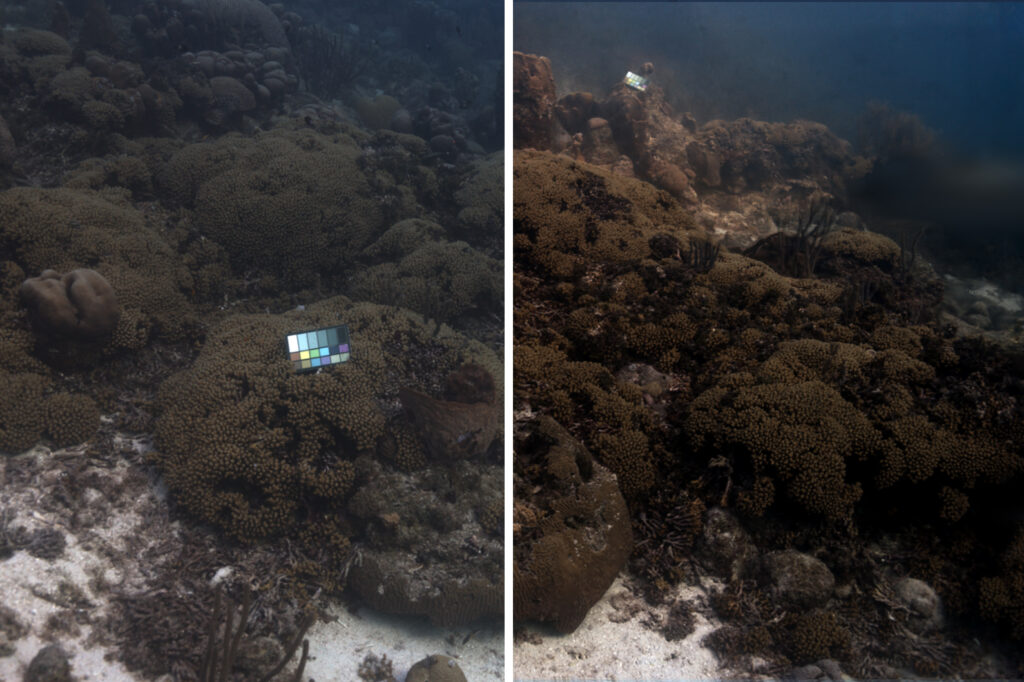

The researchers applied SeaSplat to images of the sea floor taken by divers and underwater vehicles, in various locations including the U.S. Virgin Islands. The method generated 3D “worlds” from the images that were truer and more vivid and varied in color, compared to previous methods.

The team says SeaSplat could help marine biologists monitor the health of certain ocean communities. For instance, as an underwater robot explores and takes pictures of a coral reef, SeaSplat would simultaneously process the images and render a true-color, 3D representation, that scientists could then virtually “fly” through, at their own pace and path, to inspect the underwater scene, for instance for signs of coral bleaching.

“Bleaching looks white from close up, but could appear blue and hazy from far away, and you might not be able to detect it,” says Yogesh Girdhar, an associate scientist at WHOI. “Coral bleaching, and different coral species, could be easier to detect with SeaSplat imagery, to get the true colors in the ocean.”

Girdhar and Yang will present a paper detailing SeaSplat at the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). Their study co-author is John Leonard, professor of mechanical engineering at MIT.

Aquatic optics

In the ocean, the color and clarity of objects is distorted by the effects of light traveling through water. In recent years, researchers have developed color-correcting tools that aim to reproduce the true colors in the ocean. These efforts involved adapting tools that were developed originally for environments out of water, for instance to reveal the true color of features in foggy conditions. One recent work accurately reproduces true colors in the ocean, with an algorithm named “Sea-Thru,” though this method requires a huge amount of computational power, which makes its use in producing 3D scene models challenging.

In parallel, others have made advances in 3D gaussian splatting, with tools that seamlessly stitch images of a scene together, and intelligently fill in any gaps to create a whole, 3D version of the scene. These 3D worlds enable “novel view synthesis,” meaning that someone can view the generated 3D scene, not just from the perspective of the original images, but from any angle and distance.

But 3DGS has only successfully been applied to environments out of water. Efforts to adapt 3D reconstruction to underwater imagery have been hampered, mainly by two optical underwater effects: backscatter and attenuation. Backscatter occurs when light reflects off of tiny particles in the ocean, creating a veil-like haze. Attenuation is the phenomenon by which light of certain wavelengths attenuates, or fades with distance. In the ocean, for instance, red objects appear to fade more than blue objects when viewed from farther away.

Out of water, the color of objects appears more or less the same regardless of the angle or distance from which they are viewed. In water, however, color can quickly change and fade depending on one’s perspective. When 3DGS methods attempt to stitch underwater images into a cohesive 3D whole, they are unable to resolve objects due to aquatic backscatter and attenuation effects that distort the color of objects at different angles.

“One dream of underwater robotic vision that we have is: Imagine if you could remove all the water in the ocean. What would you see?” Leonard says.

A model swim

In their new work, Yang and his colleagues developed a color-correcting algorithm that accounts for the optical effects of backscatter and attenuation. The algorithm determines the degree to which every pixel in an image must have been distorted by backscatter and attenuation effects, and then essentially takes away those aquatic effects, and computes what the pixel’s true color must be.

Yang then worked the color-correcting algorithm into a 3D gaussian splatting model to create SeaSplat, which can quickly analyze underwater images of a scene and generate a true-color, 3D virtual version of the same scene that can be explored in detail from any angle and distance.

The team applied SeaSplat to multiple underwater scenes, including images taken in the Red Sea, in the Carribean off the coast of Curaçao, and the Pacific Ocean, near Panama. These images, which the team took from a pre-existing dataset, represent a range of ocean locations and water conditions. They also tested SeaSplat on images taken by a remote-controlled underwater robot in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

From the images of each ocean scene, SeaSplat generated a true-color 3D world that the researchers were able to virtually explore, for instance zooming in and out of a scene and viewing certain features from different perspectives. Even when viewing from different angles and distances, they found objects in every scene retained their true color, rather than fading as they would if viewed through the actual ocean.

“Once it generates a 3D model, a scientist can just ‘swim’ through the model as though they are scuba-diving, and look at things in high detail, with real color,” Yang says.

For now, the method requires hefty computing resources in the form of a desktop computer that would be too bulky to carry aboard an underwater robot. Still, SeaSplat could work for tethered operations, where a vehicle, tied to a ship, can explore and take images that can be sent up to a ship’s computer.

“This is the first approach that can very quickly build high-quality 3D models with accurate colors, underwater, and it can create them and render them fast,” Girdhar says. “That will help to quantify biodiversity, and assess the health of coral reef and other marine communities.”

This work was supported, in part, by the Investment in Science Fund at WHOI, and by the U.S. National Science Foundation.